I always wanted to be a doctor.

|

| Dr. Ed, B.C. (Before Camden), a young man on the verge of greatness |

There were three men who were my earliest medical heroes and the driving forces behind my career choice: Chad Everett (better known as Dr. Joe Gannon on Medical Center), Hawkeye Pierce (MASH) and my dad, Dr. Ed Travels of Camden, New Jersey. I could not call myself a reasonable son without dedicating a blog to the man who helped make my earliest medical dreams into a memorable career. Dr. Ed-dad-this blog is for you.

Dr. Ed ran a family practice in Camden, New Jersey. Camden in the 1970's took one of the worst financial nose-dives in history of the state of New Jersey. It went from a middle American, working-class, mixed ethnic city to being one of the roughest 70's and 80's ghettos in America. Dr. Ed's office by the time he reluctantly left Camden was smack in the middle of a part of town that makes post-war Beirut look like the Central Park Botanical Gardens. It was so scary that police wouldn't go there in less than pairs. Not wanting to be the last rats on a sinking ship, Dr. Ed's medical peers started to leave the city in droves during the 1970's.

Dr. Ed didn't leave.

As a boy I remember his friends coming by our house and asking him: "Ed, why don't you leave that shithole?" He would answer, "Because I'm all they've got." And it was true. Dr. Ed had opened his office in the 1960's and twenty-five years later he had several hundred patients who filled his office every day often waiting three hours to get his treatment and advice. He never rushed anyone. Like a true old school doctor he'd look a patient dead in the eye-with a cigarette in his mouth-and lecture the patient on the dangers of smoking. And he'd be effective. Those were the days when doctors were immune to the ailments of normal mortals. I've heard this is no longer the case.

Dr. Ed didn't leave.

As a boy I remember his friends coming by our house and asking him: "Ed, why don't you leave that shithole?" He would answer, "Because I'm all they've got." And it was true. Dr. Ed had opened his office in the 1960's and twenty-five years later he had several hundred patients who filled his office every day often waiting three hours to get his treatment and advice. He never rushed anyone. Like a true old school doctor he'd look a patient dead in the eye-with a cigarette in his mouth-and lecture the patient on the dangers of smoking. And he'd be effective. Those were the days when doctors were immune to the ailments of normal mortals. I've heard this is no longer the case.

Dr. Ed had a true, palpable sense of responsibility and concern for his patients that is being systematically washed out of medical practices these days. He was the last of a line of Old School General Practitioners who were trained to handle every medical condition. He did everything from office surgery to Internal Medicine to Psychiatry. He delivered babies and even delivered the babies of those he had once delivered. When the rest of the doctors abandoned their patients and headed to the suburbs Dr. Ed could not bring himself to do that. He truly was all they had and he truly loved being that guy. He was a legend in Camden. In the middle of that horrific neighborhood where every house and apartment was busted and abandoned, Dr. Ed parked his Cadillac right on the street and no one ever touched it. In a city that looked more like a war zone than a neighborhood, he got a pass.

I loved going to Dr. Ed's office when I was a child. After getting out of his car the odor of old sewage and urine was so bad that I'd hold my nose until I was safely inside the waiting room. That stench grew worse in the Camden streets year after year. I wondered how the people living there ever got used to it. Inside the office I remember the smell of alcohol disinfectant and the latest flowery perfume of dad's secretary. Dr. Ed was always thirty minutes late by the time he got to the office. His waiting room was already twenty patients deep. I would have to run the gauntlet of hugs and fawnings from the old black ladies sitting patiently waiting for their appointments. Once inside the inner sanctum of his office it was time to play with every piece of equipment in the treatment rooms. I'd take apart the otoscopes and stethoscopes, make houses out of tongue depressors and make towering medicine bottle pyramids and knock them over. Doctoring seemed like a good time with a lot of great toys. Fortunately it still does.

|

| Look! A mountain! In Africa! |

|

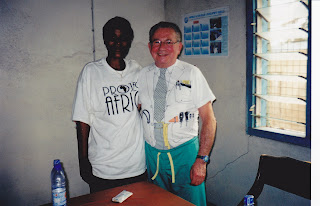

| Liberian Refugee Clinic: There's more at the door |

In 1990 thousands of Liberians left Liberia during one of Africa's most vicious civil wars. President Charles Taylor, a Bentley University educated man, had worked his way up through the government ultimately becoming president by slaughtering the current President, Samuel Doe. (Charles Taylor had previously been removed from the Liberian government for acts of embezzlement, but in the scope of African politics this kind of infraction is no worse than a few parking tickets. Infractions like this are no deterrent towards being supreme leader.) His was the rebel government made famous for making their political points by amputating the arms of men, women and children. They'd send the victims back to their villages to spread his fearful message: If you have no hands, you cannot write your vote. The result was mass exodus out of Liberia. As Liberians scattered in all directions in West Africa many made their way to Ghana. A stretch of land was made available outside the capital city of Accra. Initially the camp was designed to be temporary home to ten thousand displaced Liberians while the government was sorted out. At least twice this number showed up. In 1997 the United Nations, in an expected act of United Nationsism, withdrew all support and medical care from the camp because Charles Taylor promised to be a reasonable terrorist and gave "scout's honor" that he would hold an honest general election. The refugees were certain that execution awaited them in Liberia and stayed in the camp. In 1998 I was medical director of a Los Angeles-based charity group asked to set up a working temporary clinic that had been vacated the year previously by the UN. By then there were 30,000 Liberians living in Buduburam in a camp that was designed to hold less than one third of that number. For Dr. Ed, if this meant being back in the game, it was like being flung in the World Series. Compared to Buduburam, Camden was a walk in the park.

In 1990 thousands of Liberians left Liberia during one of Africa's most vicious civil wars. President Charles Taylor, a Bentley University educated man, had worked his way up through the government ultimately becoming president by slaughtering the current President, Samuel Doe. (Charles Taylor had previously been removed from the Liberian government for acts of embezzlement, but in the scope of African politics this kind of infraction is no worse than a few parking tickets. Infractions like this are no deterrent towards being supreme leader.) His was the rebel government made famous for making their political points by amputating the arms of men, women and children. They'd send the victims back to their villages to spread his fearful message: If you have no hands, you cannot write your vote. The result was mass exodus out of Liberia. As Liberians scattered in all directions in West Africa many made their way to Ghana. A stretch of land was made available outside the capital city of Accra. Initially the camp was designed to be temporary home to ten thousand displaced Liberians while the government was sorted out. At least twice this number showed up. In 1997 the United Nations, in an expected act of United Nationsism, withdrew all support and medical care from the camp because Charles Taylor promised to be a reasonable terrorist and gave "scout's honor" that he would hold an honest general election. The refugees were certain that execution awaited them in Liberia and stayed in the camp. In 1998 I was medical director of a Los Angeles-based charity group asked to set up a working temporary clinic that had been vacated the year previously by the UN. By then there were 30,000 Liberians living in Buduburam in a camp that was designed to hold less than one third of that number. For Dr. Ed, if this meant being back in the game, it was like being flung in the World Series. Compared to Buduburam, Camden was a walk in the park. |

| Is this culturally inappropriate or just funny? |

We met our group of charity workers at Dulles Airport in Washington, DC. Dr. Ed was sixty-eight at the time. There were a few other members of the group close to his age, but he took the role as Elder Statesman. He would hereafter be deferred to as the expert in all matters of life experience. That put a smile on his face that I'd not seen since he'd left practice. He felt needed again in a way that all doctors need to be needed to feel normal. This was Dr. Ed's first trip to Africa (I would take him on two other charity trips later to Swaziland and Ethiopia), but I didn't see any of the apprehension from him that I'd experienced during my first trip. I'm a planner and a big fan of good info and recon about a destination before I get there. Most of my destinations have significant biologic and physical threats. Dr. Ed slept peacefully during the ten hour plane ride to Ghana. He hadn't a single concern for what we were stepping into. He's always had a way of going head-first into situations, for better or worse. It defined him. I figured he had bigger stones than me, but then again he should. He's my father.

|

| Sweaty Doc |

The camp was a mix of dust, dirt and cement structures with corrugated sheets of metal for roofs. Our clinic was in the front of the camp. It was a blue concrete structure separated into four rooms. Each room had single light bulb and an ineffective ceiling fan. We'd pulled wooden tables into each room and set up a make-shift pharmacy of the hundreds of pounds of medicine we'd carried in from America. It was ninety degrees outside without a cloud in the sky. It was five degrees hotter in the clinic. I set Dr. Ed up in an examination room and assigned two local Liberian women, Fatuh and Annie, to look after him. I told them to keep him hydrated and make sure he took a break when he needed one. They doted on him like two attentive daughters and called him "Faddah." He liked that. It was 9:30 AM by the time we got everything prepared for the patients.

Dr. Ed asked, "OK, what do we do now?"

I pointed out the window to the four hundred patients lining up outside the clinic. "We start with them."

|

| Dr. Ed instructing Dr. Erik on the fine art of making rubber glove balloons |

We worked all day without a break. When Dr. Ed found an interesting case or one that stumped him he'd send one of the daughters in to find me.

"Faddah say he have somting to show you, doc Erik."

|

| When you are a bad child the doctor will eat your lollipop. |

I'd work my way through the sweaty, impatient crowd to get to his room and he'd give a passionate, technical presentation of the case to me like I was a visiting professor. Then he'd refer back to cases he'd seen through the years and tell me how they used to do it in the old days. He had that renewed gleam in his eye that I hadn't seen since Camden. He was at home in this kind of environment--desperate, difficult and challenging. He was back in the game. Every father and son have special topics in life that they can bond over. Most talk about cars or sports or Ponzi schemes. My dad and I had Malaria and Filariasis. Those were some of the best bonding moments we'd ever had.

|

| Dr. Ed: Deep in the Game |

|

| Macumba rules! |

Macumba was a nearly pitch black lounge at the end of a long dark flight of stairs, past a doorman as big as a Ghanaian house. Inside I could make out a distinct mix of three different groups of people: foreign businessmen, prostitutes from five different African countries and one wayward group of charity workers (us). It was like the barroom scene from the first Star Wars movie. The music, as promised by Big Tony, was an incredible mix of Ghanaian "high life", Jamaican dancehall and Ivory Coast "Zoblazo." I had never heard a more pristine,intense music mix in any other club in the world. I sat down with the OFC at a table in front of the dance floor. We all ordered sixty-four ounce bottles of Ghanian Star Beer (arguably the best beer in Africa). The dance floor was packed with curvy women from all over West Africa wearing clothing that were two sizes too small, providing the the least possible coverage. I looked over at Dr. Ed and Mr. Henry and reminded them that it was okay to blink once every five minutes. They just laughed and pretended they didn't hear me. After the second Star Beer jet lag and battle fatigue took hold. I was spent. It was time to head back to the hotel. The OFC laughed at my suggestion to go home. These old men called me a light weight. I let them have their moment, but reminded them that this job was a marathon not a sprint. We'd see who's still standing by the end of the week. They only agreed to leave after I'd promised we could come back to Macumba the next night after work. Big Tony said he knew a better place.

We worked for nearly two weeks at the refugee camp. Each day more and more patients showed up after hearing there were doctors and nurses working in the abandoned clinic. The lines got longer; the crowds got bigger. We treated over two thousand patients during that trip. Many patients had nothing physically wrong, but wanted to speak to someone about the horrors of their lives since they'd escaped Liberia. Dr. Ed's medical memory got a jump start during this trial by fire. I watched him savor every minute of being the King of the Clinic again. Dr. Ed and I drank a few Star Beers, saw a lot of good nightlife in Accra (highly recommended) and made some lifelong Ghanaian friends . I was happy for him--happy to get him back in the game.

|

| Proper doctoring in Africa requires proper attire |

Beautifully written tribute to your father.

ReplyDeleteI expect to be mentioned in the forward of your best-selling book as being the guy that got you started.

ReplyDeleteThis incredible tribute to your father has moved me. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteYour mother foewarded this to me, & I read most of it through my tears. I've heard much about you & your family from Shelly, & I'm really not surprised to find what a special person you are, coming from such wonderful parents!

ReplyDeleteMarilyn Benshetler

When I stop "crying" I'll tell you just how much I love you. You have really touched my heart !!!!

ReplyDeleteSome of the memories were "lost" due to the stroke many years ago, but you've recalled them for me and I love you, (although I'm still crying. Jimmie Pezzato came over and I welcomed him with wet eyes. Strange,, I don't want to call you "Rotten Kid" anymore !!!!!!! :) :) :)

I loved this story Erik. My father always respected Dr Ed as do I. You are a very luck person with a wonderful family. Hope to see you all soon.

ReplyDeleteCarol Dugan Adams...yes...thats Carol from NJ! hehehe:)

Hello Kapop and Erik,

ReplyDeleteWell you guys said that I was the one doing all of the crying when we were there...but you were right. I had just lost my husband prior to our trip..but I was also crying tears of love and happiness while we were there..Such memories..Thank you both..it was a pleasure and privilege to have been a part of it. I will NEVER forget it. Reminds me of why I became a Nurse. Love Mary Cotton

Hey Erik,

ReplyDeleteI'm a friend of Larry Fleischman's and Peter Brackman's and came across this on Pete's page. Great article and makes me think of what I can do for my dad, an aging psychiatrist - for his obligatory gesture - thanks!

This was beautiful. I enjoyed it so much. I've been a friend since about 1973 and worked with him in Camden. He was truly one of the best diagnosticians ever. He didn't need fancy equipment to know what was amiss. My family love and miss him. God grant him health and the strength to all. Fondly, Linda Hill

ReplyDelete